The importance of Dr Ambedkar

Born the 14th child of an army officer, Bhimrao Ambedkar was the only one of his siblings to finish primary school. As a member of the Untouchable caste, he was forced to sit outside the classroom for lessons, and not allowed to drink water unless someone else poured it for him. Like racism, casteism is a form of discrimination that targets people because of their descent, and is still functioning in India today.

Undeterred by the systemic opposition to his gaining an education, he went on to study at Columbia University in the United States and then the London School of Economics. In his home country however his work was constantly challenged because of his caste. He established a business that failed when his clients learned that he was an Untouchable. As a Professor of Economics in Mumbai he was popular with his students, but his colleagues still didn’t want to share a water jug with him.

Highly educated and increasingly politicised, Ambedkar fought for a place for Untouchables within society. For a decade he tried to secure for them the basic human rights to drink water from public places, to receive an education, to access opportunities to rise in the world; in short to live like human beings.

At the time of independence from Britain he was arguably the most educated man in India; an economist, barrister, social reformer, human-rights advocate, and the architect of the Indian Constitution, but discrimination and prejudice continued: petty, humiliating and incredibly hard to change.

Having spent years trying to change the system from the inside, he had come to the conclusion that the indignities and violence under which Untouchables were being forced to live were as a result of their being a part of the Hindu Community. He refused to live under this oppression, and at the Yeola Conference on 13 October 1935, stated his intention to renounce the religion of his birth. He exhorted his followers to join him in seeking a religion which would see that equality of treatment, status and opportunities were guaranteed to them unreservedly. Though he had been born a Hindu, he would not die one.

Over the next twenty years he continued to fight for rights for Untouchables in the political sphere while he considered his religious alternatives: Islam, Christianity, Parsi, Jainism, Sikhism. He assessed how each religion would benefit the converts politically, socially and economically, while also considering the impact such a mass conversion would have on the political landscape of India. He did not want his community to become pawns in the conflicts of the time.

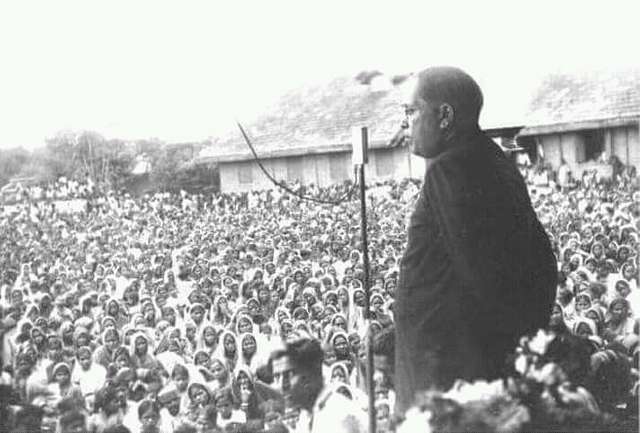

On 14 October 1956, whilst already suffering very poor health, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism: it was twenty one years and a day after his initial announcement that he would not die a Hindu. He took the refuges and precepts from the most senior monk in India, and then his followers took them from him. Suddenly there were a quarter of a million more Buddhists in India.

Just over six weeks later his health failed and he died.

For many students of political history, Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism is an anomaly, a curious by-line in the life of one of the great men of the 20th Century. Yet Arundhati Roy, in her essay The Doctor and the Saint describes this as his most radical act. In this way, Ambedkar addresses not only the social problem his people faced but departed from ‘Western liberalism and its purely materialistic vision of a society based on ‘rights’.

It was a deliberate and considered decision by a leader who brought all his intellectual and visionary qualities to bear upon the problem of caste in order to bring dignity and freedom to his people. He recognised that the problem could not be solved on its own level; it required a complete change in outlook, values and attitude to life, it had to be transcended.

For Ambedkar, Buddhism was not simply a religion, but a force for social change. The principles of liberty, equality and fraternity underpin his vision for a society with members of the Sangha “devoting [their] life to service of the people and being their friend, guide and philosopher”. This radical view of Buddhism as a tool for societal transformation continues to benefit Indian Buddhists.

In October 1956, when Sangharakshita talked with those new Buddhists he was invariably met with the response ‘we feel free‘. In spite of still being treated badly, there was a sense of agency, of independence, of something to practice and a community to develop. This is as true today as it was then. You need only listen to part of a life story from an Indian sister or brother in the Sangha to be inspired by how much responsibility they often take for their own minds despite deeply challenging conditions, and yet, for many of them, spiritual practice will be underpinned by a strength of altruism, or outward-looking concern for society that stands in contrast to a more individualist approach to the spiritual life.

The Buddha’s teaching doesn’t have to go from the psychological to the spiritual, it can also go from social transformation to spiritual transformation. In his talk Remembering Ambedkar, Sangharakshita encourages those in the west to pay more attention to objective and social issues for a more balanced spiritual life, asking us to engage with spreading the Dharma and to look towards benefitting others.

Sangharakshita draws a parallel between Ambedkar and his description of the Bodhisattva in the interview about his poem The Bodhisattva’s Reply (track 11) – for Ambedkar gave his strength to his people. He was the man that held the vision, he was an exemplar, he shows how much one individual can do, how much one person can have an influence.

Resources

Subhuti on why we honour and remember Dr Ambedkar

Vajratara talking about Dr Ambedkar

Video interviews with Ratnkumar, Yashosagar and Jnanasuri (who was there in 1956 when Dr Ambedkar and his followers became Buddhists)

Indian style Refuges and Precepts